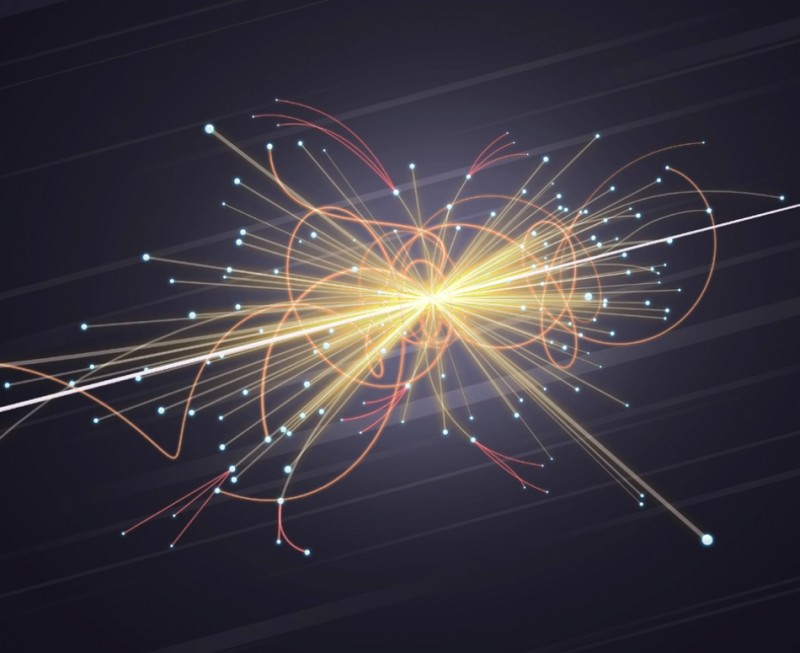

The Standard Model of Particle Physics accurately describes about 5% of the observable universe. The discovery of the Higgs boson opened a new chapter in our understanding of nature.

Are you ready to explore?

The field of particle physics has advanced dramatically during the 10 years of physics work at the LHC. Today, an integrated Future Circular Collider program, comprising the highest-energy lepton collider (FCC-ee) followed by the energy-frontier hadron collider (FCC-hh), promises the most comprehensive particle physics program that foreseeable technology can provide. A comprehensive overview of the physical potential of the FCC is presented in the FCC Conceptual Design Report (FCC CDR) volumes 1-3, downloadable HERE.

What are the fundamental interactions that govern nature?

Almost everything in the universe can be explained by four fundamental interactions. These interactions can explain the shape and structure of a galaxy, depending on the precise motion of various particles governed by the laws of gravity, or the structure of a water molecule, based on the principles of quantum mechanics and defining the laws of chemical bonding.

Our best understanding of how these particles and the three fundamental forces relate to each other is summarized in the Standard Model of particle physics.

The fundamental interactions are characterized according to four criteria: the types of particles subjected to the force, the relative strength of the force, the range over which the force is effective, and the nature of the particles transmitting the force.

Standard Model and beyond…

The Standard Model of Particle Physics (SM) is our best theory of the fundamental particles that are the building blocks of the universe and how they interact. It explains how particles called quarks, which make up protons and neutrons, and leptons, which include electrons, create all known matter. It also explains how force-carrying particles, which belong to a larger group of bosons, interact with quarks and leptons. The final building block, the Higgs boson, was discovered at CERN in 2012.

The Higgs boson explains how all other particles acquire their mass. It was discovered by the ATLAS and CMS experiments nearly fifty years after its theoretical proposal. Understanding its fundamental properties is one of the experimental goals for future colliders.

The Higgs boson’s connection to many of the deepest mysteries in physics means that it will remain a focus of research for experimentalists and theorists for the foreseeable future.

Study of the Higgs boson

The LHC has been very successful in its initial investigations of the Higgs boson’s interactions with quarks, leptons, and force carriers, the W and Z bosons. One of the main goals of the FCC program is to take these measurements to the next level, a higher order of magnitude in terms of precision. Measurements of the production and decay of the abundant Higgs bosons and other Standard Model particles produced at FCCs can investigate possible deviations from Standard Model predictions. Furthermore, it can shed light on the fundamental nature of the Higgs boson, revealing whether it is a fundamental particle or a composite particle.

The Standard Model also predicts the Higgs boson’s self-interaction. Measuring how the Higgs interacts with itself requires far higher statistics than are achievable at the LHC. FCCs can definitively establish the existence and properties of the Higgs self-interaction, given that much of nature is based on it; this is a crucial milestone. Determining the Higgs potential at the FCC has implications for many fundamental phenomena, such as the nature of the electroweak phase transition in the early universe.

The fact that the Higgs boson is located at the intersection of such a diverse range of interactions also shows that studying it offers an extremely promising avenue for uncovering clues about what might lie beyond the Higgs. The FCC integrated program provides the best possible tool for this discovery, with its wide measurement range, sensitivity, and the large number of Higgs bosons produced.

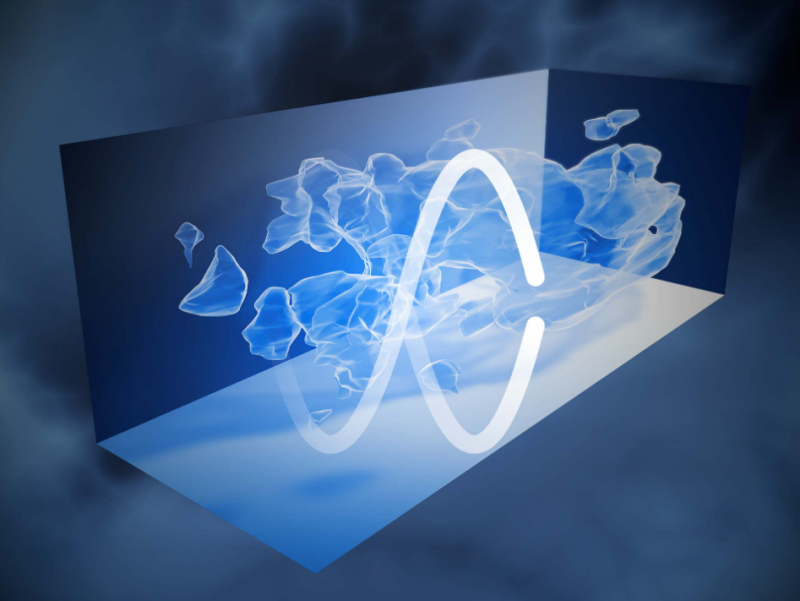

Pushing the limits of density and energy

Particle physics has reached a significant milestone. The discovery of a light Higgs boson with a mass of 125 GeV opens a new era for the exploration of physics beyond the Standard Model. Particle physics must continue its research in the broadest possible scope, with radical improvements in precision, accuracy, and energy range.

The future circular electron-positron collider (FCC-ee), to be implemented in stages between 90 and 360 GeV, will allow for in-depth study of the interactions of the four heaviest particles known today (namely, the Z and W bosons, the Higgs boson, and the top quark).

The FCC-ee provides ideal conditions (light intensity, energy calibration, ao) for studying these particles, offering numerous opportunities for precise measurements, the investigation of rare or forbidden processes, and the potential discovery of weakly interacting particles. The FCC-ee is also an excellent stepping stone for a 100 TeV proton collider (FCC-hh), for which it provides a large part of the infrastructure.

The complementary and synergistic physics programs of these two machines offer a uniquely powerful long-term vision. This vision forms the basis of the 2020 European Particle Physics Strategy.

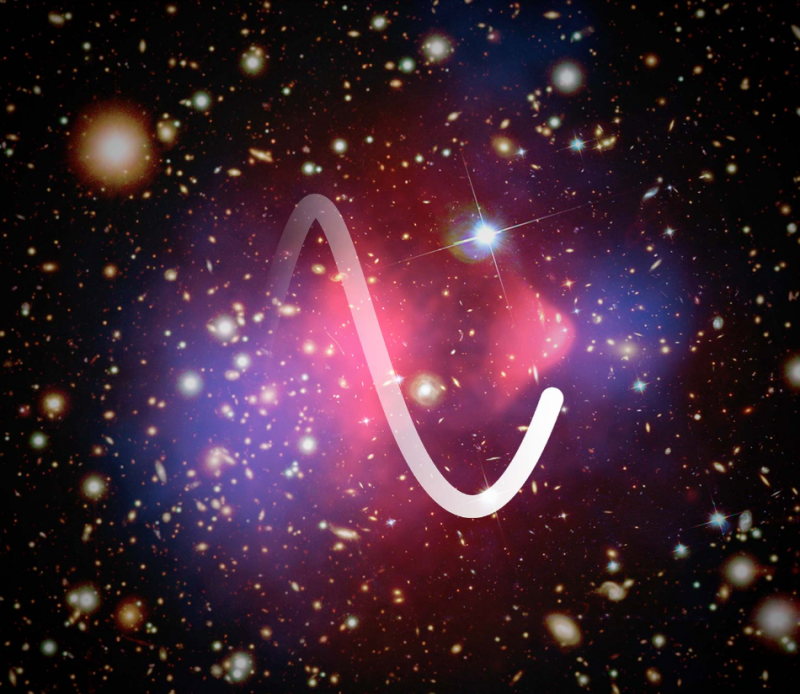

The search for dark matter?

Many astronomical observations show that the universe contains far more matter than is visible to the naked eye. Visible matter makes up only 5% of the universe’s content! The remaining 27% consists of dark matter, which gravitationally holds galaxies and galaxy clusters together.

Ordinary matter, known as baryonic matter, is composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons and is described by the Standard Model. Dark matter candidates frequently appear in theories that propose physics beyond the Standard Model and may consist of new particles yet to be discovered.

No experiment, whether in colliders or anywhere else, can investigate the entire range of dark matter (DM) masses allowed by astrophysical observations. However, there is a very broad class of models in which theory supports dark matter candidates with masses ranging from GeV to several tens of TeV. The FCC will revolutionize the search for dark matter in the form of weakly interacting massive particles and will encompass a wide range of potential signals predicted by the production of dark matter or the production of particles mediating its interaction with ordinary matter. FCC-ee and FCC-hh offer complementary avenues for searching for dark matter, which may consist of lighter particles (i.e., sterile neutrinos) or be produced in Higgs boson decays.

Why do neutrinos have mass?

One of the fundamental experimental questions in modern physics is how neutrinos acquire their mass, as this is not predicted by the Standard Model.

In the first decade of the new millennium, modern neutrino experiments provided the first evidence of a phenomenon called neutrino oscillations, showing that neutrinos possess a small mass. According to the Standard Model, neutrinos are massless particles; therefore, this discovery marked the first crack in the Standard Model. In 2015, Takaaki Kajita and Arthur B. McDonald were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their “significant contributions to experiments showing that neutrinos change identity.”

The crack isn’t large enough to completely shatter the Standard Model because we don’t know what produces the tiny neutrino masses. FCCee has a unique opportunity to shed light on this issue. Neutrino masses, if they exist, may be produced by their heavy antiparticles called Heavy Neutral Leptons, which would be generated through the decay of Z bosons. In its initial phase, FCCee will generate trillions of Z bosons, enabling it to search for these particles down to the electroweak scale.

Why is there more matter than antimatter in the universe?

Another experimental piece of evidence pointing to the need to continue exploring the physics of subatomic particles is that matter outnumbers antimatter. Approximately 14 billion years ago, the Big Bang, the event that gave birth to the universe as we know it, created equal amounts of matter and antimatter. However, the universe is now entirely composed of matter, and antimatter is nowhere to be seen. The question, “Where did the antimatter disappear to?”, is one of the most important unanswered questions in particle physics to date. Explaining the origin of cosmic matter-antimatter asymmetry is a challenge at the forefront of particle physics.

We know that nature can create matter-antimatter imbalances through an event called CP violation. The problem is that the amount of CP violation we measure in current experiments is insufficient to explain the state of our universe. Therefore, the prevailing idea addressing this imbalance is to assume the existence of a new source of CP asymmetry. FCCee, thanks to its enormous integrated radiation, will be able to investigate new sources of CP violation. With FCC-hh, the FCC must definitively investigate the novel conditions required by a strong first-order phase transition that supports the dominance of matter in the universe.

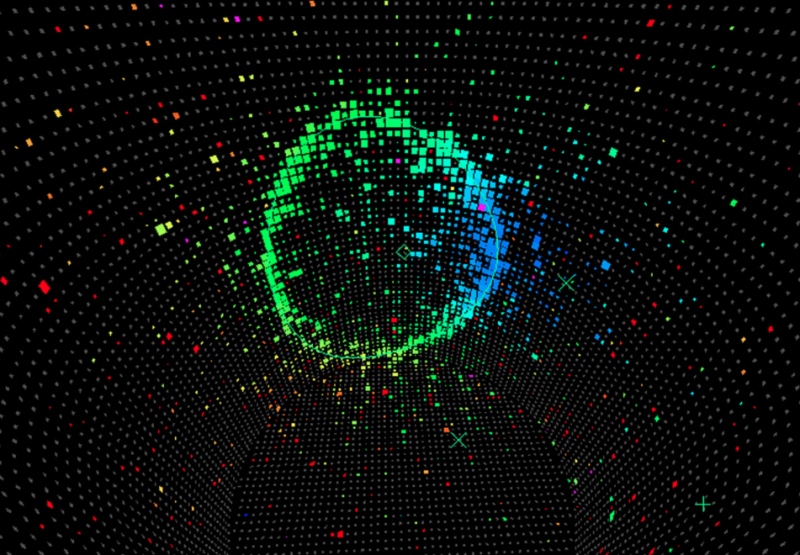

Are you looking for supersymmetry?

Experiments have repeatedly confirmed the Standard Model of particle physics. However, the model is incomplete. Among other things, it cannot explain dark matter, the small mass of the Higgs boson, or why the interacting forces between particles do not converge at high energies. These are some of the questions that supersymmetry could address. The simplest supersymmetric theories—those that best explain the Higgs boson—predict a large number of supersymmetric particles accessible to the LHC.

Theorists introduced the concept of supersymmetry in the 1960s to link two fundamental types of particles found in nature: fermions and bosons. Roughly speaking, fermions are the components of matter, while bosons are the carriers of fundamental mental forces. Supersymmetry would give every known boson a heavy “superpartner,” which is a fermion, and every known fermion a heavy partner, which is a boson.

The lack of any evidence of supersymmetric particles at the LHC so far makes it seem as though SUSY (supersymmetric symmetry) is interesting, it doesn’t seem to describe our universe. Future research at lepton and proton colliders will further constrain current scenarios and place increasingly tighter limits on SUSY candidate particles. Research can benefit from data collected at FCCs (Federal Colliders), as this data will allow for better discrimination of Standard Model backgrounds and provide more information for event reconstruction. Data collected during the FCC’s experimental program will help test different manifestations of this theory and guide theoretical thinking.